Offshore from Cannes, on the largest of the Lérins Islands, Ile Sainte-Marguerite, the musée de la Mer occupies the oldest part of the Vauban style Fort Royal.

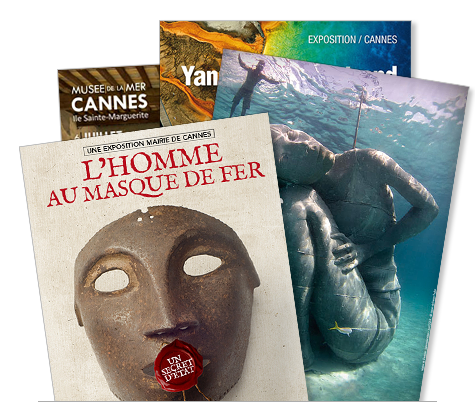

Designated as a historic monument, it is surrounded by pines and eucalyptus and juts out over the sea. You can visit the state prisons and the famous cell occupied by the Man in the Iron Mask where the mysterious prisoner was held for eleven years, as well as the Huguenot Memorial and the murals created by Jean le Gac on the theme of the painter as a prisoner.

In the Roman cisterns and on the first floor, the museum displays collections of terrestrial and underwater archaeology, as well as Roman and Saracen shipwrecks from Tradelière and Batéguier.

An area devoted to summer exhibitions opens onto a vast terrace overlooking the sea; facing the Cannes coastline and the Southern Alps at Cap d’Antibes and Estérel.

Based in the most imposing building of the fort, the so-called Le Vieux Château which was built in the 17th century, the museum stands in the oldest part of it built on Roman and medieval ruins.

Visitors can now explore the Roman cisterns that form the museum's ground floor galleries. Rocher Tower was built on the corner of the building in the Middle Ages to protect the island from regular Saracen attacks. It was raised around 1860 with a semaphore to send telegraphs.

The fort became a state prison at the end of the 17th century where people posing a threat to the monarchy (protestants after the Edict of Nantes was revoked, secular blasphemers etc.) were imprisoned on the king's request, without trial, and prisoners incarcerated on their family's request. The most famous was the Man in the Iron Mask. A wing was added to the building in 1690, bringing the number of ground floor cells to six.

Made famous by Voltaire and Alexandre Dumas, the Man in the Iron Mask is one of History's best known prisoners. This "prisoner whose name no-one knows, whose face no-one has seen, a living mystery, shadow, enigma, problem," according to Victor Hugo, enthralled generations of historians and novelists.

He has been given around sixty different identities, the most fanciful being that of Louis XIV's twin brother. Nowadays it's seen as an eccentric idea but it's still a favourite among Hollywood blockbusters.

He spent twelve years imprisoned at Pignerol Fortress (from 1669), six in Éxilles, eleven years at Fort Royal on Sainte-Marguerite Island (until 1698) then five years in the Bastille in Paris where he died in 1703 and is buried. After his death, his belongings and legendary mask (could it have been made from velvet or leather with metal fixtures?) were burnt.

The Man in the Iron Mask's keeper, Saint-Mars (Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars), the governor of all the fortresses he was incarcerated in, may have been behind the legend of the unknown prisoner.

The letters he sent to Louvois, the Sun King's minister, about the prisoner made him sound important and he boasted of being the keeper of the realm's greats, as he was once for Fouquet and Lauzun who were imprisoned on a whim by Louis XIV.

The Man in the Iron Mask had no trial, police records or prison records but was denied the freedom to be seen by anyone and remained at Saint-Mars' mercy for 34 years.

The Man in the Iron Mask was locked away in Sainte-Marguerite and only spoke and revealed himself to his keeper, Saint-Mars. He was only allowed to leave his cell for daily mass before an altar in the hallway near his cell door. Nothing remains of his prison furnishings but it had basic furniture, wall hangings and floor rugs. The prison was meant to be comfortable and the fire was always lit in the hearth. Nothing is left of the famous Iron Mask, apart from the mystery of the man behind it.

After the Edict of Nantes was revoked (1685), those who refused to renounce were subjected to terrible consequences: massacres, torture, struggle, kidnapped children, imprisonment and more. Six of the Refuge's pastors who had illegally returned to France were imprisoned in the fort on Sainte-Marguerite.

There's a memorial in their cells in tribute to the martyred pastors imprisoned on Sainte-Marguerite. Supported by the French Protestants' History Society and Pastor Charles Monod, the first cell was inaugurated during pentecost in 1950 with the help and involvement of Dutch protestants. The ceremony was attended by Pastor Marc Boegner, President of the French Protestant Federation. A second cell was installed with the help of the Genevans the following year. The memorial was moved to join the Musée de la Mer in 1985.

Four cells in the prison corridor extension, west of the Man in the Iron Mask's cell, lost all trace of their prisoner residents, tiling, plaster, graffiti all erased forever. All that remained was the architecture in the empty space that Jean Le Gac had spent time in.

"When I used to imagine going to prison to paint in peace a few years ago, it was never serious because I wasn't really under any illusion about the possibility of devoting myself to my art among the prison guards and sexual misery; just being able to think about it only proved what little room for manoeuvre I had between my family and material life...

... It came to mind whilst visiting the island, as I walked down the long path lined with eucalyptus alongside the museum curator who introduced me to the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask and the long history of the fort's Arab prisoners: Khalifa Mohamed Ben Allal Sidi Embarek's family, servants and treasurers... Khalifa's first secretary Kaddour Ben Rouyla's family with their slave woman of colour right at the bottom of the register... Chentouff Caïd de Oued el Barmmam and not forgetting Belal "of colour" emancipated from their service... Dahbou Ouls el Bachir's deceased brother's family... and many more. On the one hand I had a faceless man, on the other I had too many names, facts and history and this gnawing desire to be locked away to try to accomplish one last effort in concentration, to pierce the fine membrane holding me back from the unique piece I feel has been in me for so long...

... I began painting in prison cells on July 2nd 1992 with the state of mind of the voluntary artist prisoner." Jean Le Gac

Île Sainte-Marguerite has no spring. The water supply issue must have come up as soon as people settled here.

Several cisterns built in Gallo-Roman times are still in the fort today. The museum cistern is one of them. It has 4 vaulted rooms. It is the last remnant of the original hydraulic system. A model details an attempt to replicate the entire system. Rainwater collected from the tall building's rooftop (e.g. a temple) was channelled along an aqueduct to a basin above the cistern. One or more orifices in the vaults filled it (you can still see the orifice in the second vaulted room) then the collected and stored water could be distributed using a distribution box (water tower) to supply fountains, baths, basins, pipes etc. with water. The hypothetical hydraulic system is based on several examples existing in Gallo-Roman urban planning. Subsequent excavations and surveys will help correct and modify it.

Extensive ancient ruins were unearthed during work inside the Fort Royal on Ile Sainte-Marguerite in 1972. Fourteen excavation programmes between 1973 and 1993 established the site was occupied between the 6th century BC and 4th century AD.

After being restored by the CNRS Centre d’Etude des Peintures Murales Romaines (Roman Mural Research Centre), some of the fragments from the murals in a laconicum (Roman hot room) exhumed during excavation went on public display in a 1st floor museum gallery in 1997.

This wreck was found 50m deep east of Ile Sainte-Marguerite near the small island of La Tradelière in 1971 (discovered by M.A. Pastor and M.A. Roudil). The ship's cargo was wide-ranging. Nine different types of amphorae were identified. An extensive cargo of terracotta and glass tableware, nested goblets stacked on top of each other, little vases with zoomorphic patterns and a series of glass cups in different colours formed the rest of the haul.

Aside from the wine in amphorae from Chio and Cos, Greek islands in the Aegean, the La Tradelière boat shipped brine (Spanish brine amphora), dates and thousands of hazelnuts scattered all over the site. The wealth and variety of the goods helped form the hypothesis that the La Tradelière shipwreck may have been one of very few ocean-going ships from the Eastern Mediterranean, Greece and Dodecanese Islands to capsize on the Ile Sainte-Marguerite's reefs.

This shipwreck was found 54m deep on the western tip of Ile Sainte-Marguerite in 1973 (discovered by Jean-Pierre Joncheray). The ship is assumed to have caught fire then capsized based on the molten pitch on several ceramics and pieces of burnt hull. Pottery forms the majority of the cargo. The assumption is that it was commercial freight due to the variety of styles and smaller than normal sizes. The pottery fulfilled all kinds of functions: storage jars of all sizes, from very large ones to little ones, pots and pans, vases for liquids and oil lamps. More unusual items were also found among the otherwise standard collection: a drum, chandelier with seven dishes, camel-shaped lamp filler and pots with coverplates. Delicate oil lamps, fine pitchers with wide spouts and pots with sieves provide unrivalled evidence of how the 10th and 11th century Muslim world had a perfect understanding of technology and style.

Entrance ans exit of the Fort Royal.

The bastion is a projecting defensive part of a fortification's structure and key to the "bastioned" fortification that first appeared in 16th century Italy. It makes enemy crossfire easier and is filled with earth to cushion the impact of cannon balls.

This church was dedicated to Saint Joseph in 1658 and replaced an older place of worship which had become too cramped for the fort's growing population (the soldiers and their families). It has a tribune on the upper floor. Its painted decorations have been restored in accordance with the originals.

The curtain is a section of wall between two bastions.

This building was used as a gunpowder storehouse. It meets very strict building criteria to prevent the powder being 'set off' by accident and to keep it dry. With a thick, 'bomb-proof' vaulted ceiling, it is protected by a hollow bastion and cannot be seen from outside the fort.

This gate was the main entrance to the Royal Fort in the 17th and 18th centuries and was defended on the ditch side by a 'demi-lune' or ravelin.

The demi-lune is an "advanced" defensive work built in front of the wall to protect a gate or a curtain. That was often where the enemy focused its first attack.

There was once no drinking water at the Royal Fort. Since ancient times, the inhabitants of the site had built several huge cisterns and a system for collecting rainwater. This 17th century well with its pyramid-shaped roof also has cisterns.

A building designed to house soldiers, with a long central body (the soldiers' sleeping quarters) flanked by two two-storey lodges (accommodating officers and non-commissioned officers). The Royal Fort barracks are not open to visitors.

The parade ground is an area inside the fort kept free for assembling a troop of soldiers.

Located in the most imposing of the fort's buildings, the museum occupies two separate areas:

The fort continued to be a prison after the French Revolution. Several hundred opponents of the colonisation of North Africa were detained there (1841-1884 approx.), including the smala of Abd el-Kader and Kabyle insurgents.

On display at the museum are archaeological objects from excavations on land and under water, such as fragments of ancient mural paintings (Iron Age and 1st century) and the cargo of two shipwrecks found off the island (Roman shipwreck from the late 1st century BC and a 10th century Saracen shipwreck).

From 1972 to 1986, 14 archaeological digs unearthed significant remains dating back to the 3rd century BC. There are 2 types of remains which can still be seen in the excavation trench:

This terrace was built on Roman remains (cryptoportico) and converted into a bakery in the 17th century. It was named after Marshal François Achille Bazaine. Charged with treason during the Franco-Prussian War, the marshal was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment at Sainte-Marguerite, but made an extraordinary escape ten months after he arrived.

Note in passing the wells on tanks and the remarkably well-preserved watchtower, (the building that juts out on the corner of the rampart where the watchman took up position).

Point Info Biodiversité®. CPIE des Iles de Lérins et Pays d’Azur.

Centre International de séjour Îles de Lérins.